That value system translated in the deforestation of much of the North American continent for farms.Īs time passed, the colonists built mills and towns. When I studied Colonial American history at Yale University, I was suprised to read the many references in the journals written by the colonists that expressed this attitude toward the land. They also believe that God brought them to this new land to vanquish and to "use" it.

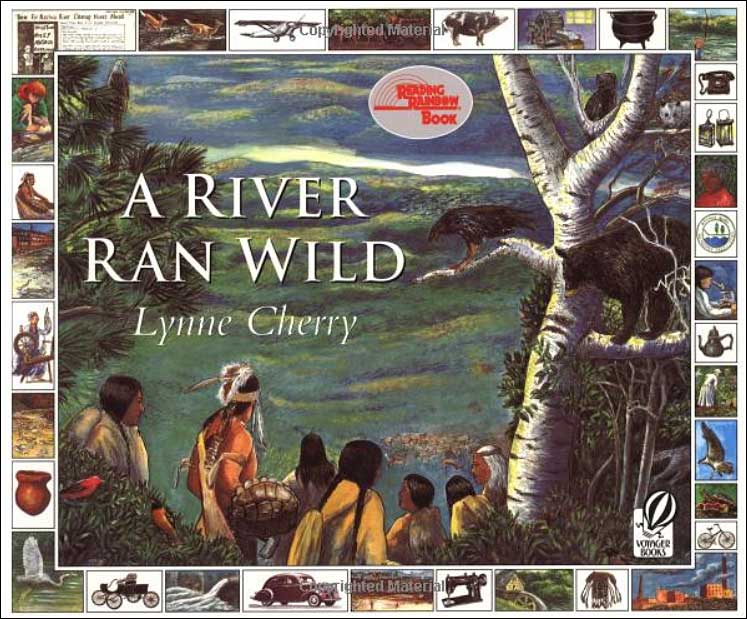

The european colonists bring with them a very different value system: they think of nature as something to conquer and as trees, a set of commodities to buy and sell for profit. The Nashaway indians think of themselves as part ofnature and are grateful for the clean drinking water and good fish to eat that the river provides them. All in all, an excellent picture-book examination of the the history of one river, one which offers some sobering facts, but also some inspirational figures! I think I need to learn more about Marion Stoddart.A River Ran Wild begins with the first native americans deciding to settle upon its banks. The artwork is lovely, and I enjoyed looking at both the larger paintings on each two-page spread, and the decorative borders, with the many animals and items mentioned (or hinted at) in the narrative.

I appreciated the contrast drawn between the Native American way of interacting with the natural world, and the European (and then Euro-American) way - complementary versus adversarial - as I think this clarifies why environmental degradation was allowed to take hold, and to continue for so long in this country. Until, that is, the 1960s, when an activist named Marion Stoddart decided she had to do something.Ĭhosen as one of our September selections over in The Picture-Book Club to which I belong, where our theme this month is "ecosystems," A River Ran Wild is part history, part science, and all parts engaging. Show More pebbles on the river-bed could be seen from above, thus explaining its original native name, the Nash-a-Way, or "River With the Pebbled Bottom" - through its first harnessing (in order to power mills) during colonial times, and then its use as a dumping ground for waste during the Industrial Revolution, Cherry charts a trajectory that leads ever downward.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)